There Are Long Term Effects To Missing Info On Birth Records

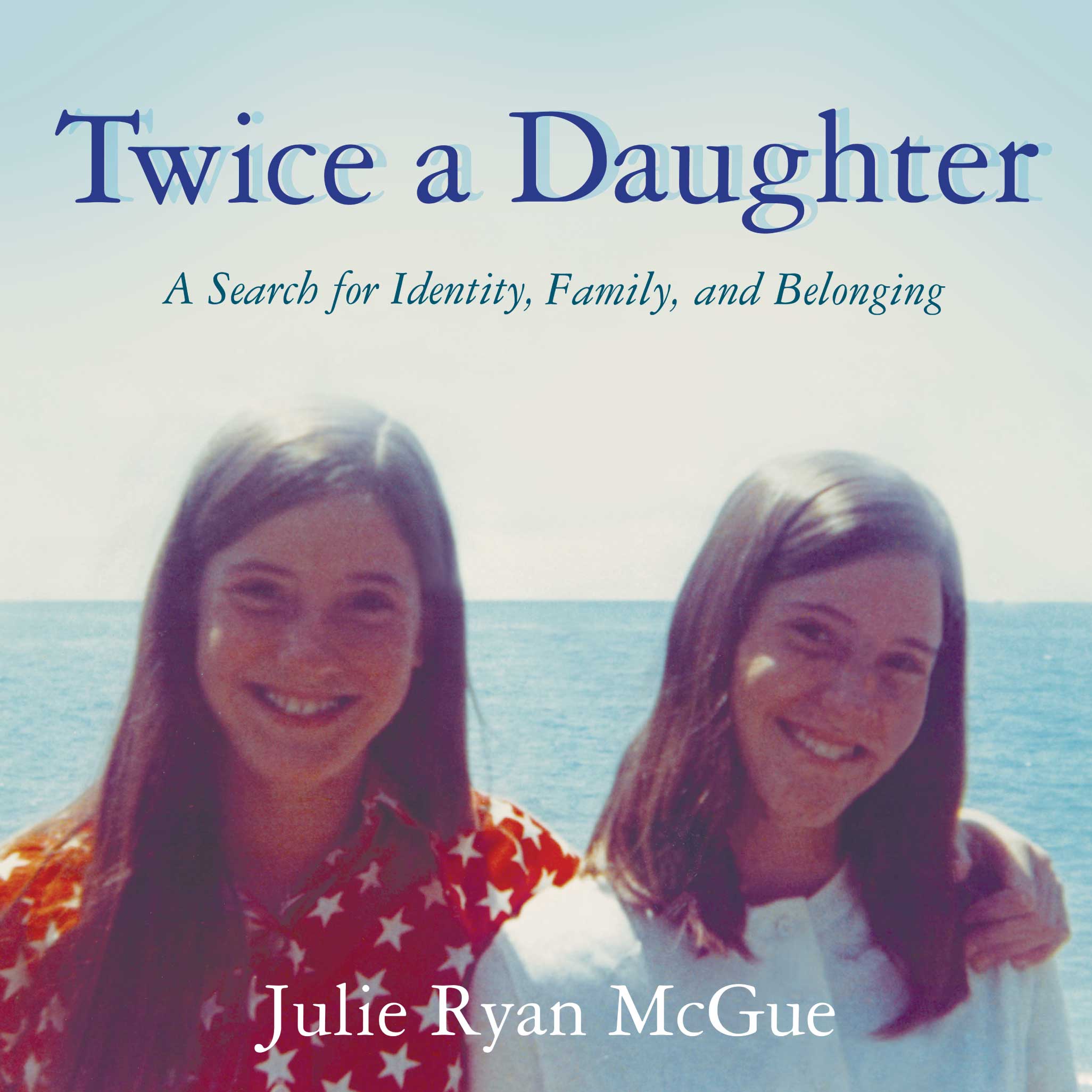

Julie McGue

Author

Here’s what happened. After first denying contact with me, I waited eight months to connect with my birth mom. Having a complete medical history and family tree was important to me, not just for myself, but also for my four kids. So, in the first phone call with my birth mother, I mustered up the nerve. I asked her how she met my birth dad, and then I requested his identity. She puzzled over the spelling of his last name, but eventually offered up his full name, as well as, some identifying information that would come in handy later on. I was ecstatic. My family tree was filling out.

The search for my biological father lingered on for over a year. I came to believe that either my birth mom had remembered incorrectly or she had lied about his name. Thanks to the tenacity of a genealogist in Minnesota, his correct identity was unearthed. Once my birth mom learned I’d found my birth dad, she admitted to her lie, and that the mistruth was due to fear: fear of him reappearing in her life. Okay, but not okay. To shorten a very long tale, my birth dad never acknowledged being my biological father. Lucky for me I inherited a half-brother willing to undergo DNA testing with me. And, genes don’t lie.

Once my new brother and I matched, besides being thrilled that I had a new brother and sister, I discovered that I was of Chippewa descent. This startling realization felt like one of those television Ancestry.com ads. Being Native American had never been on my radar. I have light brown hair, fair skin, freckles, and hazel eyes. My looks scream Scotch-Irish or Danish, both of which also appeared on my ethnic pie chart.

I dove head first into the notion of being a Chippewa Indian from Minnesota. Again thanks to my new brother, I became privy to a myriad of details relating to my Native American lineage. I am a direct descendant of a union between a Chippewa princess and a Scotch Irish fur trader. Together, my great-great-great grandparents produced a slew of sturdy folk that settled the northern part of Minnesota; their names appear in state history books. So proud was I to be related to these people, that I took the next step. I delved into the requirements to become a legitimate member of the Chippewa tribe.

As I mentioned at the outset of this post, my birth father’s name does not appear on my birth record. That fact alone means that I am not and will never be a bona fide Chippewa. Denied. My biological father’s identity had to be listed on my birth record in order for me to claim membership in the tribe. While adoption customs and procedures in the 1950s officially protected the privacy of my birth parents, the rigid protocol has repeatedly prevented me from legally claiming my personal story.

My inability to be recognized as a Chippewa isn’t the biggest heartache I’ve ever faced, but I am disappointed. This is is just another roadblock offered me through adoption. Over the course of the last eight years, the inaccuracies on my OBR have profoundly affected my ability to connect with my heritage. The same applies to my four children.

The long-term effects of the mistruths on the OBRs of adoptees from the closed adoption era are far reaching. Isn’t it a darn shame that adoptees, like me, can’t claim to be what is in our blood, because of the decisions made by adoption gatekeepers in the last century? Isn’t it time to reverse those errors?

I’d love to hear what you think.

“Isn’t it a darn shame that adoptees, like me, can’t claim to be what is in our blood, because of the decisions made by adoption gatekeepers in the last century? Isn’t it time to reverse those errors?”

Snag my in-depth reference guide to best equip you for the journey ahead.

0 Comments