When the honeymoon is over:

Growing the birth parent-adopted child relationship

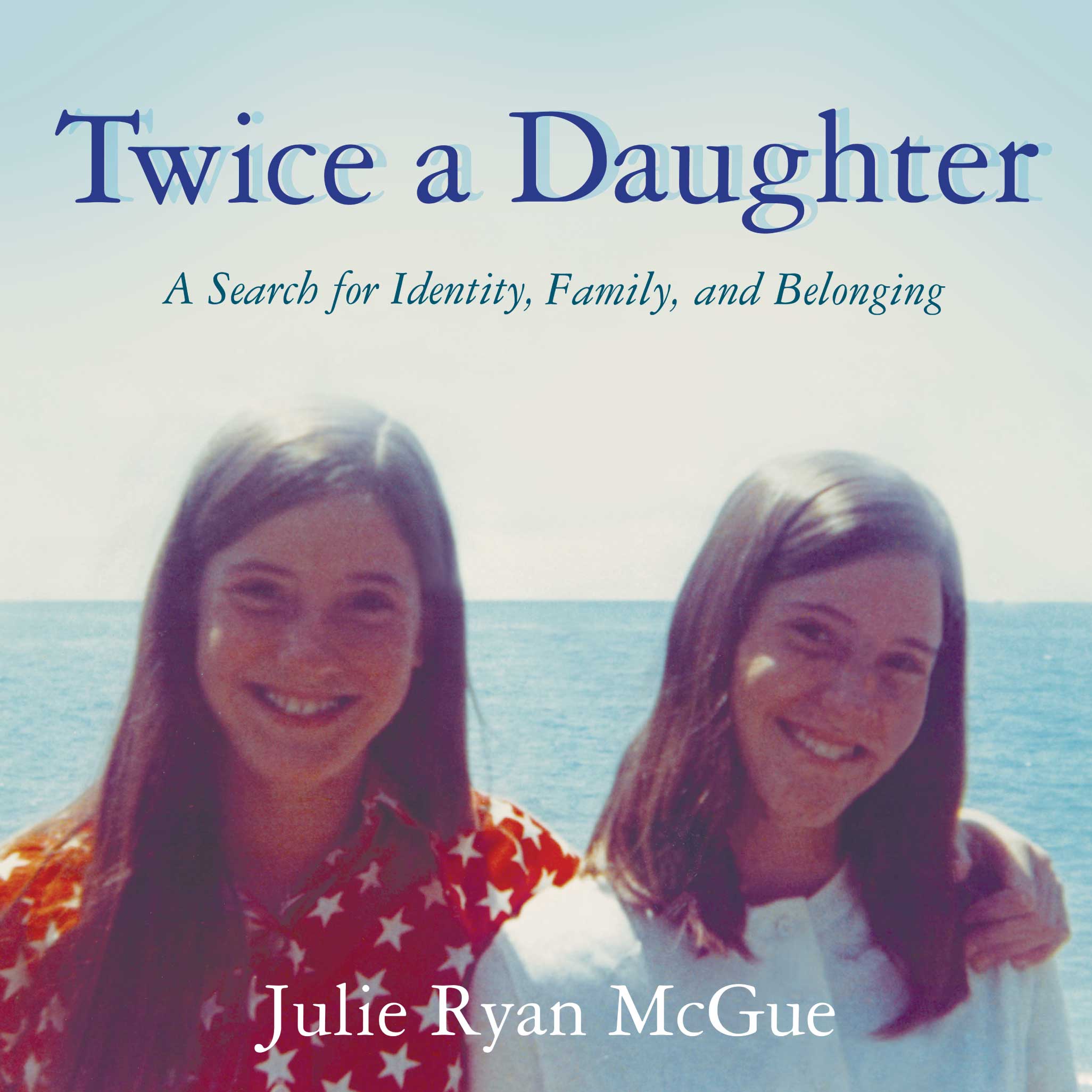

Julie McGue

Author

“Secondary rejection” is a well-known term in the adoption world. It refers to the disappointment, hurt, or rejection that adoptees and/or birth relatives experience as they attempt to connect with family members they lost to adoption. The first rejection is adoption itself, which adoption writer, Nancy Verrier, aptly termed the “primal wound.”

A secondary rejection shows up when:

– a birth mother is reluctant to share the secret of an unplanned pregnancy with a spouse or family member

– a birth parent or adoptee declines to facilitate introductions to relatives and friends

– health history and background information are not exchanged

– birth relatives are unwilling to inform/include biological family in daily activities, holidays, or special events

Secondary rejection is also a phone call that goes too long unreturned, or a letter that goes unanswered for months. These slights, big or small, are yet another wound to a heart that is already compromised.

When I first reached out to my birth mom in 2011, I experienced my first secondary rejection. It came in the form of a terse note to my intermediary. My birth mother denied contact with my twin sister and me, and then she demanded that we never reach out again. It took me months to peel myself off the ground. As a mom myself, I couldn’t understand how a mother could treat her child in such an unloving, disrespectful manner.

Eventually, my birth mom changed her mind and phoned the intermediary to initiate contact. Our first get together was glorious, mind-boggling, and affirming. Within weeks, our relationship blossomed; the sensation was much like falling in love. The honeymoon period of our reunion continued for months, but then the inevitable happened. I experienced unreturned phone calls, misinformation, and a refusal to widen the circle of “who knows.”

The first time my twin sister and I visited my birth mom in her new senior living complex, she asked that we phone her when we arrived and to wait in the lobby. We were told not to sign in at the front desk. Over lunch at a nearby cafe, she confessed her fear about our writing in the center’s guestbook. Next to our names was an obligatory space for “relationship to resident.” She admitted that no one at the senior center knew about the two daughters she had born out of wedlock and placed for adoption. After lunch, we strolled back to her apartment. To everyone we encountered in the hallway, she introduced us as “relatives visiting from Chicago.”

When I returned home, I called the social worker who leads my post adoption support group. She reminded me to treat myself with kindness and to surround myself with people who behave in a loving manner. And once I was ready to establish a healthy connection with my birth mom, I needed to set boundaries with her.

I worried, of course, that my pushback would anger my birth mom and jeopardize our relationship. I picked up the phone, and as I had been coached to do, I expressed how her recent behavior had marginalized me. She made no apology and hung up. Months elapsed before we spoke again.

During our estrangement, I wore down the soles of my sneakers. I reflected. I meditated. I journaled. And I never missed an adoption support group meeting. At these sessions, the social worker, my fellow adoptees, and birth mothers in attendance helped me to understand something important that would help bridge our impasse: the trauma of being an unwed mother in the 1950s, and the safeguarding of that shameful secret for a lifetime had formed my mother’s personality and behavior. Her pain ran deep. That would never change. Nor would her fear of being judged and shamed by those around her. If I wanted to stay in a relationship with her, I needed to compromise.

The reunion with my birth mom is now in its second decade. My sister and I achieved this milestone by shifting our expectations. In turn, my birth mother is more considerate of our feelings. For our relationship to have reached this stage of growth, we had to let hurt and anger slip away and allow compassion to fill the void.

Now that we have surmounted these obstacles, I grieve for my birth mom. I grieve for all of us, because of all that transpired and all that might have been.

“For our relationship to have reached this stage of growth, we had to let hurt and anger slip away and allow compassion to fill the void.“

Don’t miss a blog post!

Receive my blog posts directly to your inbox.